Jack Horner can dispense with his mad scientist franken-chickenosaurus machinations. We already have plenty of fine and dandy carcass processing theropods in all corners of the world - land and sea - right now, thank you. In my last post, Allosaurus - More of a Vulture Than a Falcon, I described a remarkable convergence in several lineages of carcass rendering birds that use a macabre feeding technique I have dubbed "choanal grinding". This feeding method in turn inspired a theorized feeding technique in Allosaurus that I outlined and referred to as the "bonesaw shimmy" - the shimmy being a dance based upon rapid alternate movements of the shoulder, outlawed due to it's overtly sexual nature in the 1920's . This "bonesaw shimmy" in turn may yield implications for other theropods to varying degrees I suggested.

In this post I want to expose a known anatomical characteristic linking past and present carcass rendering theropods (forgive me for using the term theropod loosely as such, for me it implies both extant aves and Mesozoic theropods/paraves/true avialians unless otherwise specified) . This characteristic - which is so painfully obvious it has hid in plain sight - has the potential to offer much utility in inferring likely feeding behavior and technique in both Mesozoic and Cenozoic theropods.

But as I am one with a little bit of a penchant for theatrics, I do not want to introduce that overlooked anatomical characteristic just yet but instead let us first spend some time with the bearded vulture aka the Lammergeier (Gypaetus barbatus).

|

| Lammergeir. credit unknown but too cool not to share |

Impressive, no? And for some nice footage of bearded vultures at a feeding station. If you squint your eyes a bit, not too hard to imagine dromaeosaurids or unenlagines in the clip below.

If you are still smitten with the regal beauty of these birds here is a nice close up video (the first pic of this post is a screen grab from it).

Now maybe you have never spent that much time up close and personal with these birds until now. They are astonishing - and that strong dinosaurian vibe you get off their appearance is not a mistake. Whether or not you keyed into the anatomical congruence that unites 230 million years of carcass rendering theropods yet is ok - you probably subconsciously sense it.

What I am referring to - the uniting anatomical peculiarity - is the supraorbital ridge or brow ridge if you will present in this and many other carcass rendering birds and Mesozoic theropods. Relatively obscured in the lammergeier due to feathers it is more noticeable in the lappet-faced vulture below giving it that distinctive "evil" glare. Not coincidentally (as I will discuss) the lappet-faced vulture is a large vulture with a penchant for the particularly tough and gristly parts of carcasses as well as a noted predator.

|

| lappet-faced vulture.ccsharealike2.0. credit KCZoofan |

|

| CA condor skull. credit Kai Schreiber. CCsharealike2.0 |

|

| Southern Giant Petrel skull. credit OVAM. CCbylicense |

|

| note the "eagle eye" brow ridge. CC3.0 credit Graham Curran |

|

| eagle skull. credit Kai Schreiber. CCsharealike2.0 |

The tops of Mesozoic theropod heads are also adorned with an array of crests, eye ridges, lacrimal horns, knobbly protuberances and often times fairly thick bone deposits. In fact you can take a fairly base model crest such as you see on Coelophysis or Allosaurus and the vast majority of predatory theropod heads are but slight deviations.

| Coelophysis bauri |

|

| credit Witmer's Lab |

|

| Mapusasaurus roseae showing the thick lacrimal/nasal crests along top of skull. credit Kabachi CC2.0 |

Instead I am going to offer an alternative explanation: These structures - although potentially co-opted for display, combat, sun shielding - had their impetus not for any one of these reasons but were generated for biomechanical reasons.

The biomechanical origin for these structures lays in absorbing stresses and strains from strenuous feeding activities.

Again, let me get a little nuanced here because I think nuance is sometimes lacking in these types of discussions and people get hemmed into either/or debates. For sure, in critters like Dilophosaurus or Monolophosaurus these structures are custom built as display structures. But what I am suggesting is that if a structure is in fact a display structure - it is usually obvious. And in the vast majority of theropods the head gear is a lot more conservative and primarily serves a mechanical function.

If we look at the theropod head it is a compromise between strength and lightness of build. The head had to be strong enough to interact and sustain integrity through vigorous encounters with prey/rivals. But it also had to be as light as possible to facilitate the rapid neck driven feeding mechanisms that were fairly ubiquitous across the group. The lacrimal horns, ridges, rugosities etc etc. serve as "energy dumps" where the stress and strains encountered across the mouth are transferred up and away and "dumped" into the thick deposits of bone and pneumatic cavities at the top of the skull. A study of stress and strain distribution in the skull of Allosaurus pretty much spells it all out.

Note how in the above visual (from Rayfield et al. looking at forces in the skull of Allosaurus) that compressive forces marked "yellow" are being concentrated towards the lacrimal, nasal, frontal bones up those struts of bone away from the tooth row. Most telling is the pic on the bottom right where the course of the compressive forces appears to be literally tracing the crest line on the top of the skull of the allosaurus. In fact if you take a second to look at the architecture of a theropod skull holistically - it appears biomechanically designed to move stress/strain away from the tooth row towards the top of the head. This makes sense for a predator that needs to bite stuff and does not want to suffer mechanical failure of its teeth/jaw. Excessive forces can be shunted away towards thick crests/nasal bosses/brow ridges etc etc. Not only that but it minimizes the deposition of heavy thick bone throughout the whole skull - which would add cumbersome weight - and maximizes the animal's ability to move its head quickly and efficiently.

|

| credit Scott Robert AnselmoCC3.0. Trex |

And you can see this thickening of the top of skull to full effect in the pic here of T-rex. A mechanical design begetting thick theropod crests. If we accept the maxim that form follows function the mechanical advantages of such a design elegantly explain the long tenure of the design.

Why has no one has approached the issue of why certain theropods have converged on such thick lacrimal/nasal/orbital ridges before is a good question. Maybe we just are taken in by the cool factor of it - they do add a bit of style and flair to their look. But, as I always tell my traffic school students, things have a way of hiding in plain sight.

Ok, so if my hypothesis has merit - that these structures serve as "dumps" for excessive forces incurred during vigorous feeding bouts - then a good test would be to see if said structures are diminished or absent in theropods that feed on small prey, fish, or have explored a more omnivorous or herbivorous lifestyle.

|

| Ornitholestes hermanni. Osborn 1903. AMNH 619, holotype from Carpenter et al. 2005 |

|

| Masiakasaurus knopfleri. |

|

| Suchomimus.creditAStrangerin theAlps.CC2.0 |

Suchomimus tenerensis. Usually interpreted as a fish eater, although an opportunistic small/medium game predator is likely given the dino/pterosaur consumption shown in close relatives. And don't be fooled by the notion of "mere fish eater" either. Some of these fish on the menu were huge with heavy, ganoid scales. So in spinosaurs we see a single crest with some pretty thick looking bone as well as some nice ridges around the eyes. So although not as heavily crenulated/crested as carcharodontosaurids. allosaurids, tyrannosaurids and other large game hunting theropods there is still some amount of crest/ridge action consistent with the stresses likely incurred from a diet of small/medium game and large armored fish. Prediction met.

What is interesting is what we see in terms of headgear on several other medium-largish theropods that have also been suggested as occasional to frequent consumers of fishy - aquatic type prey. The species I am referring to are Dilophosaurus wetherelli - which Kirkland has been advocating as a fish eater for years - and Ceratosaurus nascicornis of which Bakker, more controversially, has been interpreting as a fish (esp. lungfish) predator for a while now.

|

| credit Jaime A. Headden aka Qilong. CC3.0 |

|

| Ceratosaurus. credit Tremaster. CC2.0 |

And what about dromaeosauridae? Well they run the gamut. But the pattern seems to hold up. Regardless of how big they are, dromaeosaurids with reduced serrations/adaptations for small game are relatively impoverished in terms of strong head gear while dromaeosaurids with serrated teeth/deep skulls/homodont dentition aka "classic ziphodont" styled animals have relatively robust headgear. I am going to concentrate on two extremes.

One of my favorite dromaeosaurids is the South American unenlagine Austroraptor cabazi (Novas, 2008). The long low snout, conical dentition lacking serrations, and general build have inspired comparisons to spinosaurids - which became extinct at that point as far as we know in South America. So despite it's size Austroraptor appears to have been another small/medium game specialist with adaptations that speak to this. And if this is the case according to my theory it should fall short in terms of robust head gear comparatively speaking. Although it has a bit of rugosity on the top of the skull and some supraorbital/crest action it definitely falls short compared to true ziphodont theropods. Prediction met.

|

| Austroraptor cabazi credit Esv. CC3.0 |

|

| Bambiraptor feinbergi or baby Sauronitholestes?. credit Thesupermat. CC3.0 |

Dispense with your notions of what the size of the animal implies - this animal was punching above its weight. Check out the deep skull. And those teeth, if you look at them closely they are not conical small game teeth but stout, serrated chompers. This little bastard must have been the bane of dinosaur nesting colonies. At this size (size matters) we might not expect the crest to be as sturdy as in larger ziphodont theropods but there is a nascent double crest arising along with a thickening lacrimal area anterior to the orbit - very analogous to the suggestion of a crest in the birds that I started this post with.

If we look at a ziphodont dromaeosaur that is a little bigger, such as Deinonychus, we should expect to see a relatively more sturdy development of head gear. Prediction met.

|

| Deinonychus. credit onfirshwhois. CC3.0 |

Erlikosaurus andrewsii lacks a double or even single crest along the top of the jaw but it does have a bit of lacrimal bone thickening evident along the margin of the orbit. All in all though this animal does not have the same extent of thick crests/supraorbital ridges in ziphodont theropods. Prediction met.

I am not going to go into oviraptorids, avimids, or orhithomimids because their skulls have diverged substantially from the basic theropod design while therizinosaurids still maintain the same basic shape as other carnivorous theropods. But feel free to check out their skulls, they are lacking or diminished in robust headgear compared to ziphodont theropods.

But now I want to follow another line of inquiry this time into Cenozoic theropods .... errr birds .... errr what is the difference again? What I want to look at is extinct carcass rendering birds of the Cenozoic. If this hypothesis has merit we should see increasing robusticity at the top of these skulls in the form of solid crests, supraorbital ridges, lacrimal thickening, thick brows etc. etc. Luckily enough we have two great test groups - teratornids and phorusrhacids.

And what do you know, when we take even a cursory look at terror bird skulls the prediction is met.

|

| Titanis walleri. credit Amanda. CC2.0 |

|

| Andalgalornis CT scan. credit Witmer labs CC2.5 |

A number of features pinpoint phorusrhacids as not only hearkening back to Mesozoic theropods in some sort of vague way, but I will argue that in form and function phorusrhacids are actually directly analogous to their Mesozoic brethren - especially Allosaurus. But that is for a future post. Let's just say for now that I doubt these were mere small game hunters...

And now on to the teratornids - a group that I am especially fond of because of their ubiquity at a location not too far from me, the La Brea tar pits.

To no one's shock the skull of Teratornis merriami has a strong ridge of bone right above the eye as showcased in the above picture from the La Brea Tar Pits Blog.

|

| Teratornis merriami credit Ellen. CC2.0 |

Originally I wanted to include more detailed discussions on these two groups in this post but upon seeing how long this post already is I think it will be more practical to dedicate several future posts to both the terratornids and the phorusrhacids respectively. If you paid attention to my last post where I introduced a novel technique among modern flesh rendering birds it should not be too hard to guess what I will infer for both groups. Additionally, in doing so rectify some of the excessively conservative interpretations that have been dominating thought about how these birds fed.

To further embellish my point, that the reason for the bony protuberances, nasal/lacrimal crests and horns in theropods are not just there to make them look wicked but serve a biomechanical outlet for excessive stress, I want to point out that similar features are present in the skulls of other even more distantly related ziphodont predators.

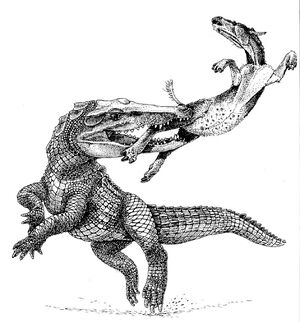

Baurusuchus salgadoensis - the terrestrial croc of late Cretaceous Brazil was sporting some fashionable brow ridges.

_2.jpg/694px-Baurusuchus_salgadoensis_(MPMA)_2.jpg) |

| credit Marco Aurelia Esparz CC3.0 |

|

| credit Robert Bakker |

|

| Postosuchus credit Mark Byzewski CC2.0 |

|

| Batrachotomus kupferzellensis. credit Gedogeheo. CC3.0 |

|

| Prestosuchus chiniquensis. credit Vince Smith. CC2.0 |

|

| Perentie (Varanus giganteus) credit Flyingtoaster CC3.0 |

Is it just a coincidence that multiple lineages of Mesozoic theropods, terrestrial ziphodont crocodiles, pseudosuchians, several lineages of extinct/extant carnivorous birds, and monitor lizards all converged on similar headgear designs? I don't think so. This convergence is due to similar solutions to similar mechanical problems incumbent upon ziphodont skulls in both feeding and grappling with large prey items.

.jpg/1280px-Majungasaurus_crenatissimus_(2).jpg) |

| Majungasaurus crenatissimus. credit James St. John. CC2.0 |

Support me on Patreon.

Like antediluvian salad on facebook. Visit my other blog southlandbeaver.blogspot

Watch me on Deviantart @NashD1. Subscribe to my youtube channel Duane Nash.

_1.jpg)