As I anticipated, reaction to my Hellhound rex bulldog lipped Tyrannosaurus rex argument was mixed. Some liked it, some were equivocal, and some were vehemently against it. You should know by now I have more than a little flair for the dramatic and don't think for a minute I have played my full hand when it comes to extreme "lippage" in theropods... That being said I took - for me at least - a very cautious, muted and tentative tone in that post. Not being naive and knowing full well that the backlash yet to come and the strong culturally entrenched reaction against extreme "lippage" in theropods going right to the heart of our cherished and idealized view of these animals... the struggle is real.

So in this post I am going to eschew that waffling, tentative tone and go right in for the kill shot. Yup names will be named. Things will get messy. Feelings might get hurt. Reputations might get questioned. Including my own but that's ok I am willing to play the villain.

But...

I did go through some real searching in how I wanted to approach this post. I mean the good and bad thing about blogging is you can see where and how traffic gets shuffled to your site which means that you get to read the things people say about you - and it does affect you deeply. In various form I have been called overly speculative, aggressive, a bit of a bully, not to be taken seriously, and sort of a mean and angry guy. And I get it why people say these things about me. I have always indulged in what I consider plausible speculative possibilities. I fully admit that I have a bit of chip on my shoulder that has a lot to do with not getting recognition and blogging not being recognized as a form of science communication on par with the "peer reviewed word" but I think that is changing. I have no problem calling out the "luminaries" of the field when they leave out data, make less than ideal suggestions, and use the weight of their name as a bully pulpit. At the same time I am fully confident that if you spent any amount of real time in the flesh with me you would come away with a perhaps very different or at least more nuanced impression of me than the above characterizations. I have also seen it written that I am too passionate and excited about my own ideas. "Too passionate and excited"... think about that for a second.... I've said it before and I'll say it again there is a little too much tone policing in paleo these days when passion and excitement are discouraged. If you have not noticed science is in a war and is failing to create the excitement, fun, enlightenment, fullfillment, and yes mysticism that other forms of belief are giving people for better or worse.

Never the less it is a hard thing to tell someone that a significant chunk of their life's work is obsolete and you have to be just a little bit of a bully to do so.

To quote the great "Nature Boy" Ric Flair: "To be the man you gotta beat the man!! Whoo!"

To really s - p - e - l - l it out for you I am make the allusion to "professional wrestling" to evince the level of venom, anger, and aggression in my heart - none at all really. It is all a bit of a bluff theatrical arrangement. Of course tone has a way of getting misconstrued in writing. And no, I am not on cocaine.

That being said I am really going out to pick a fight on this one and you better believe I am coming in swinging, guns blazing, and with the gusto!!

There is a bit of a problem in sabertooth paleontology. An echo chamber has evolved where one man and one man only seems to dominate the narrative over this eco-morphological grouping of animals. And that man is Mauricio Anton whose books, papers, artwork, and blogging have cast a heavy influence on our view of these animals. Truth be told he deserves the recognition and there is good reason for this respect. His artwork is captivating and in a class of its own. His books are well written, engaging, and straddle the difficult line between being overly technical and approachable. However when the artistic and scientific leanings of only one man become the main voice heard or recognized that is never a good thing in any social or scientific activity. Biases can and do slip through. Unconscious memes passed on.

In the case of this one aspect of sabertooth predators that I will be addressing the cultural transmission of this meme has gone on and on for some time now, Anton as the de-facto principal conveyor of sabretooth aspect and imagery merely inherited it from Knight and paleoartists/paleontologists of the past. It is not really his creation. However Anton "is the man" in sabertooth paleobiology and paleo-art. Heavy lies that throne and any reappraisal of sabretooth anatomy and imagery can not eschew mention of his influence. There really is no way to avoid going through him.

Enough beating around the bush, it's time for Mr. Sabertooth Tiger to get some self respect, stop walking around all exposed, have some decency AND COVER UP THOSE DAMN DAGGERS!!

Yup, sabertooth predators its time to grow up and cover yourself properly with nice big luscious lips sheathing your cherished daggers. You know, like is the case for EVERY EXTANT MAMMALIAN TERRESTRIAL CARNIVORAN. Is that phylogenetic bracketing enough for you? Truth be told phylogenetic bracketing should never be looked at as the ultimate truth, just a rough road-map. It is always better to take a pluralistic approach imbuing the EPB with a heavy dose of adaptationism - Stephen Jay Gould be damned. That is the approach I took with my last post on a heavily lipped T. rex and it is the method I will take here. One caveat of the adaptationism approach is that the feature you are looking at should be one that has a strong influence on survivorship and hence sexual success. So yeah, I think a feature intimately influencing, protecting, lubricating, and assisting in killing via those precious daggers counts in that regard in a very robust way.

"But what about elephants, walrus, and other tusked mammals? Their teeth are exposed all the time."

You know, I have to admit to throwing up a little in the back of my mouth whenever I hear this argument trumpeted out again and again. First of all it is moving further and further away from the extant phylogenetic bracket. We already have tons of living extant carnivorans to infer from, all of them cover their teeth completely or mostly. Even the clouded leopard the cat >most< often compared or likened to sabertoothed predators covers its teeth with a nice set of lips. Secondly, tusks don't even compare in form or function to saber toothed canines. Tusks are robust, coarse choppers for plowing into trees, roots, gouging into sediments, and >most importantly< fighting with and intimidating rivals. That they are always exposed has a lot to do sexo-social signalling. Sabertooth canines do none of these activities, are often serrated, and are intrinsic to survivorship. Tusks are always out and on display because a better strategy for always getting into costly and risky fights is to bluff your way to the top by always having your weaponry out, exposed, and in full view. Sabertooth daggers were not sexo-social displays and/or fighting tools, an argument Anton (among others) has summarily dismissed. Finally tusks keep growing in many animals that have them. Sabertooth predators had no such luxury. Comparing sabertooth daggers to tusks is like comparing a surgeons scalpel to a machete - a machete that keeps growing back. As you can tell I don't take this argument very seriously. In fact I would call it special pleading.

We already have numerous and unequivocal osteological evidence of direct evolutionary pressure on sabertooth predators to sheath and protect their cutlery.

Above you see examples of the bony correlate in all six of the respective sabertooth predator radiations; gorgonospid synapsids; thylacosmilidaen metatherians; machaeroidinean creodonts; nimravidaen carnivorans; barbourofelidaen carnivorans; and felidaen carnivorans.

It is in the form of the mandibular flange. In some examples it is quite profound, in others it is a little incipient. However it occurs in all radiations of sabertooth predators giving us a strong example of convergent evolution. But to expect evolutionary pressures to exert an influence on just the mandibular, inferior section of the tooth and not expect protection from above - where blows are most likely to come from? Evolution are you drunk? Should we really expect evolutionary pressures to exert an influence on protecting just the bottom aspect of the dagger and not the top? Really, you think so? When you blink does your eyelid only cover half of your eyeball? Does a turtle carapace only protect half of the turtle? Does your cranium only cover half of your brain? Sounds like a very half-assed protective strategy to me.

Instead I would argue a much more robust inference is that ALL sabertooth predators protected their cutlery from above and below. Some species show evidence of the inferior protection via the mandibular flange which itself was sheathed in a very rugged and durable layer of "skin" a lot like the darker area of the jowls you see in your own pet dog. The upper protection would come from a fleshy expansion of the upper lip region - just as you see in any felid or carnivoran today - except larger. As sabertooth predators evolved larger and longer daggers so to did the soft anatomy that protected and assisted them evolve in tandem. Pull up the upper lips to expose teeth and bite. Let lips go loose when teeth are not in use. That a Smilodon with big droopy facial lips seems shocking now is only an artifact of the cultural shock of multiple decades of toothed exposed iconography.

Such protection would not be 100% but I would hedge my inference in favor of protection rather than not. If a feature can evolve that can assist in the struggle for survival, then it should be there.

"How dare you compare sabertooth lips to the lips of artificially selected dogs and cats? Stop it."

Nope, not stopping. The reason I posit this distinctive bulldog looking Smilodon is that artificially bred mammalian carnivorans aptly demonstrate that there is a lot of plasticity in the facial region of these animals. That humans bred them this way for looks, for better scenting abilities, for whatever... I don't really care. All that these domestic breeds show me is that giving the evolutionary context and pressures (i.e. fleshy lips to protect large dentition) there is the genetic potential in mammals that such a look >could< evolve in a wild extinct sabertoothed animal. That the bulldog look comes about is, well, try drawing a sabertooth yourself and the only prerequisite is that the teeth are mostly or completely covered by lips and it is hard to avoid the bulldog look.

Extensive Lips & Fleshy Oral Tissues Allows Enhanced Proprioception of Sabertooth Head & Daggers in Relation to Prey. We Have Direct Osteological Evidence Of This Too.

As tool using, reduced canine having primates I think we often fail to appreciate the risks incumbent upon biting down into something that does not want to get bitten into. I mean, it is a pretty simple thought but revelatory at the same time. You are literally ramming your most vulnerable external body part into another organism latching onto and often holding onto them. Let me restate that again: your most vulnerable body part is in direct line of fire for whatever you are attempting to latch onto. Remember you have to do this again and again to make a living so to speak ecologically. All of these pitfalls would be especially true for sabertooth predators which seem to show a penchant for not only large, strong and retaliatory prey but direct and relatively prolonged contact (i.e. not a bite and flee predator but a tackle, subdue, and bite predator) in which their vulnerable daggers are put into jeopardy. If there is ANY advantage you can potentially and reasonably evolve that helps you to make a killing safer, quicker, and more efficiently then that evolution will likely occur and the inference is a robust one.

Large fleshy lips and oral tissue not only provide a better means of protection from struggling prey (although not 100%) but they also provide a larger and more extensive tactile surface area to position the teeth for efficient and safe biting.

Let me just quote Anton directly here from his book Sabretooth (pp 178-79 Sabretooths as Living Predators):

"One consistent feature of most sabertoothed carnivores is the relatively large size of the infraorbital foramen... (discussion of potential muscular insertion, rodents, Barbourfelis)... there are other structures that pass through infraorbital in all mammals - specifically, the infraorbital nerve, veins, and arteries. The infraorbital nerve is a branch of the maxillary nerve, and it provides sensory nerve endings to the whiskers. Once the nerve crosses the canal, it begins to branch; and when it reaches the roots of the whiskers, it forms a true "nerve pad," creating a characteristic swelling on the sides of the muzzles of many mammals. Thus, one tempting explanation for the large diameter of the opening in sabertooths would be the presence of very well developed, especially sensitive whiskers with rich innervation."

While Anton later tempers his stance mentioning issues of direct proportionality he does mention that " the relationship between the development of the foramina and the function of the infraorbital nerve is widely accepted among zoologists."

I would go further and posit that the reason the infraorbital foramen is relatively larger in sabertooths than other predators is that not only was the "nerve pad" more sensitive - it was also absolutely larger than the nerve pad in extant felids. Why such a large and sensitive nerve pad would be needed in these predators is fairly obvious in terms of making precise and safe incisions into struggling and retaliatory prey that could easily snap off or damage your cutlery.

Anton pp 179:

"... the killing bite of sabertooths must have been quite precise in order to avoid accidents involving lateral torsion or hitting a bone in the prey, which could cause the sabretooth to break a canine. Since the target area of the bite would be outside the predator's visual field, the tactile information provided by the whiskers would be especially useful for the precise control of the biting motions. Modern cats are able to move their whiskers thanks to well developed piloerector muscles, and during the killing bite the whiskers are usually directed forward, enveloping the bitten area in a sensitive net of hairs (Leyhausen, 1979). Given the additional risks imposed by fragile sabers, improved perception would be a useful trait for the sabretooths."

I like and agree with everything Anton says here. I just differ from him in inferring an absolutely larger "nervepad" that would ultimately be more adaptive than the smaller nerve pad he prefers that only partially cover the daggers as depicted in his and all others' paleoart. I can already picture some people saying "well what if the whiskers were just longer?" nah, always better to have the tactile ability and protection. That is the more adaptive and reasonable inference not whiskers creeping down like daddy-long legs.

As you can see in the above pic of a cheetah throat clamping Thompson's gazelle - in which the canines clamp shut the windpipe and kill by suffocation - the sensitive nerve pad is deeply enmeshed in this activity. Indeed as the bite occurs in a blind spot for the cat it is the nerve pad, especially via the whiskers, that most accurately dictates to the predator where and how the clamp should be applied. Let's think about this for a second. Many modern large felids clamp the windpipe shut with their relatively stout and blunt canines. That is a pretty refined and delicate approach and the utility of having the sensitive muzzle and whiskers enmeshed in close proximity to the bite area is self evident. However when we contrast this method with how sabertoothed predators - especially the "dirk toothed" cats likely killed - they were looking to inflict massive trauma to the general fleshy region of the neck (but also possibly abdomen). Whether the killing stroke severed arteries or the windpipe or both not really important as the end result is the same - death. So if you think about it the killing method of such sabertooth predators is less precise than many modern felids - as long as they get their bite in the general non-bony area of the neck (or abdomen) they good. SO WHY WOULD THE INFRAORBITAL FORAMEN BE RELATIVELY LARGER IN SABERTOOTHS? The logical conclusion is that the "nerve pad" was not relatively more sensitive per surface area than modern felids, it was in fact absolutely larger than modern felids and likely equally innervated and fed with adequate blood supply. This soft tissue adaptation would cover up those precious daggers and provide the tactile support to place the daggers in the right spot to make a killing stroke without risking torsional twisting of prey or bone chipping.

Additionally when we consider how this biting action would look and function in a sabertooth with the traditionally depicted modest sized nerve pad a real dilemma occurs. Due to the large size of the daggers - especially extreme in genera like Smilodon - the sensitive nerve pad would be scrunched up and pushed away from the bite area and not very useful for "feeling out" the best place to position a bite when the mouth was open. Indeed it would be the large teeth "feeling things out" - exactly the problem sabertoothed predators want to avoid!!

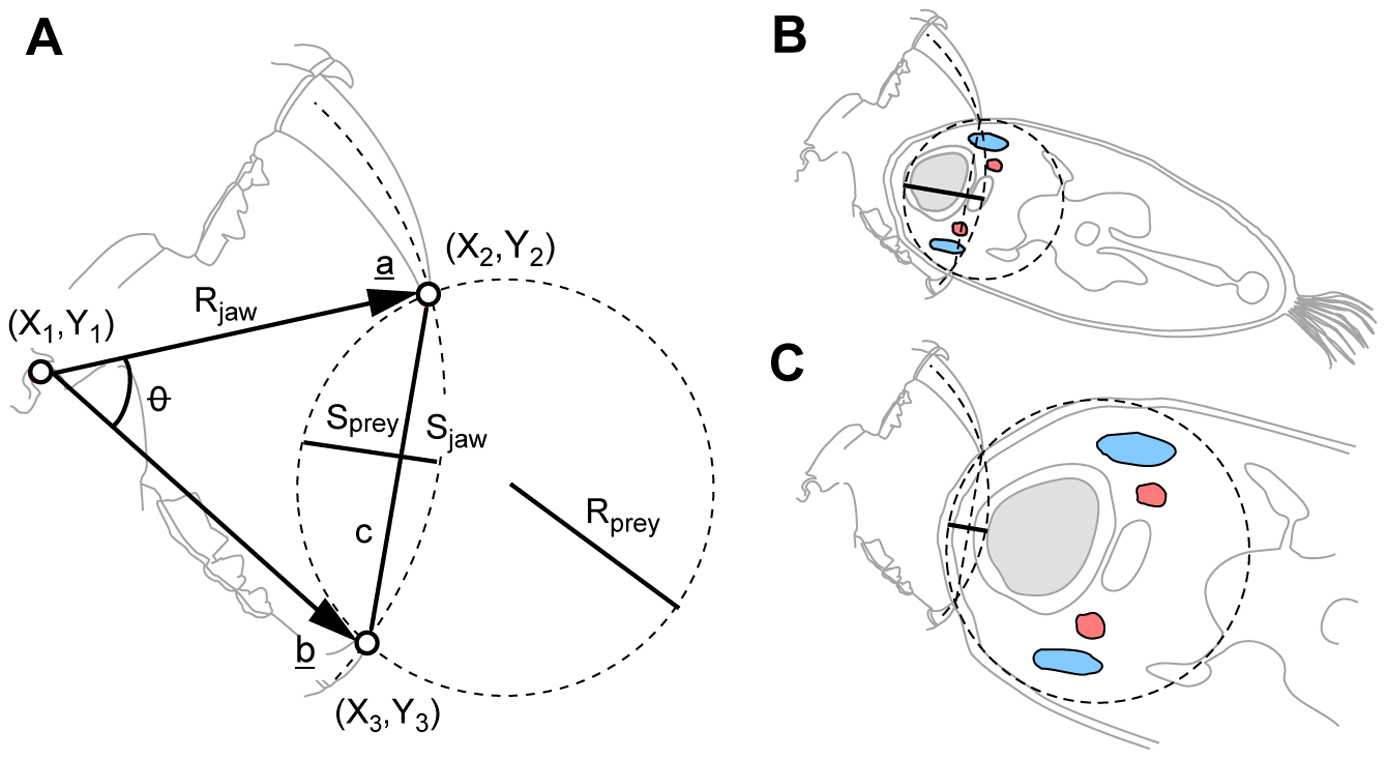

You can easily see what I am talking about using this kinematic illustration above. The sensitive nerve pad would be nowhere near the bite area in traditionally depicted sabertoothed predators. But if we infer a large upper lip and nerve pad that completely or nearly completely sheathed the upper teeth even when the mouth is opened then you have a much more efficient and safer ability to "feel out" where and when to engage the teeth with prey. In this manner the teeth are protected and sheathed until the final split second before impact and the upper lip is pulled back to reveal the daggers. The tough and elastic lip need not even be pulled back that far because as the daggers are plunged into prey the body of the prey itself would simply push back against the lip sliding them back further. Large upper lips provide the most safe, efficient, and osteologically corroborated method of biting possible.

"If only we had evidence for sabertooth appearance via cave-art or other ancient depictions" ... well maybe we do.

Yup it is time we revisit the potential Rosseta Stone of sabertooth life appearance: the paleolithic statuette from Isturitz.

Now I want to make it clear - this is an artistic representation by Mauricio Anton based upon the rendering of Czech paleontologist Vratislav Mazak who himself saw representations of the original statuette in 1970. Long story short nobody actually has the statuette as it has been lost since at least the early part of the 20th century. As the statuette has been lost and been redrawn at least two times, maybe even three times as Mazak himself is said to have only seen "representations" of it, the logical conclusion is that there is a lot of ambiguity in this piece. Furthermore as the original piece can not be directly observed i.e. it can not be "tested" by others it should be in fact stricken from scientific discourse. I mean, am I wrong? Is that not the argument put forth why "private fossil specimens" can not be part of the recognized science as they can not be first hand analyzed, observed, and tested by all parties... am I missing something here? Never the less the Isturitz statuette representation has made it through peer review and is part of the "recognized" scientific literature despite the inability to test it (peer review fail #1).

In his paper reconstructing the musculature and facial anatomy of Homotherium latidens (Anton, et al. 2009) steer away from Mazak's interpretation of the Isturitz statuette representing a late surviving Pleistocene Homotherium and instead side with the original interpretation of cave lion. In Facing Homotherium Brian Switek summarizes their argument succinctly:

It should be noted that this analysis dovetails into the facial reconstruction that Anton et al perform on Homotherium in the same paper.

Compared to:

And a cave lion representation:

While Anton et al. do provide some compelling arguments concerning body proportion and the lack of a sloped back in the model as Homotherium would have in life (sort of like a spotted hyena) these gross anatomical inferences can be explained by the lack of forefeet in the statuette which may influence how the posture is meant to be; the possibility the figure represents a dead or lying felid; and simple errors on the part of the artist.

On the chin argument I find it less than compelling that the strong chin and large lower jaw represents the tuft of hair on a lion. It just looks too prominent and large in my eyes and is more consistent with the mandibular flange of Homotherium. There is no abrupt transition from the chin to the neck line as should be expected if the chin was simply a tuft of hair. Furthermore the manner in which Anton et al reconstruct the jaw in Homotherium is inconsistent with how we or most animals actually hold the jaw in neutral pose. They pose it in "extreme" jaw closure as if the animal would be walking around clenching its teeth shut - similar to the argument put forth on extreme jaw closure in tyrannosaurids and other theropods debunked in my last post. I suspect most animals (including you as you read this unless you are like really mad right now ;') have their jaws just slightly agape in the neutral pose. This would dissuade the need for the teeth to fit into pockets of flesh in the lower jaw as suggested by Mazak and argued against by Anton et al. (sort of like male baboons) but instead the whole upper canine would simply be sheathed by the upper lip/nerve pad. When the jaw was fully closed it would simply lie against the thick tough, elastic, and lubricated skin of the lower jaw. Just like a clouded leopard which, by the way looks to have canines at least as big or bigger as Homotherium relative to its head size.

There is a bit of a tendency in paleo for people to see beautifully rendered muscular and skeletal reconstructions of extinct animals and take them a little too literally. When in reality there is a lot of guesswork and biases at play in even the most "rigorously" reconstructed extinct animal no matter how aesthetically appealing. In the paper Anton et al. provide a list of references for how they reconstruct the soft tissue for Homotherium latidens:

"For soft tissue reconstruction we followed the methodology outlined in our previous works (Anton, 2003; Anton & Galobart, 1999; Anton & Sanchez, 2004; Anton et al., 1998; Turner & Anton, 1998)."

Notice any pattern there? If a guy with the last name of Anton is the lead author of the paper and the source methodology for reconstructing soft tissue is also culled from a guy with the same last name it is not unreasonable to suspect a certain unanalyzed bias to seep through? Could there be a bit of an echo chamber here?

Anton et al., also cite the extant phylogenetic bracket as defined by Witmer as a means to infer soft tissue. But what this method lacks is putting soft tissue through the lens of adaptationism.

Anton et al. also assert that if the canines are long enough they should be seen passing past the upper lip. As evidence for this assertion they cite one example of a canine peeking past the upper lip in a dead lioness they dissected.

Now, you need not be a statistician to realize that when N=1 that is not a very large pool of a sample size to draw meaningful data from. Additionally, you need not be a mortician to realize that when stuff dies things change. Muscles grow tighter drawing back soft tissues. Mouths clench shut potentially. Anton et al. did not account for this or even mention these obvious pitfalls on drawing anatomical conclusions from a cadaver of one sample size (peer review fail #2 ). Better to look at live animals. And when you look at live carnivorans - especially felids - the upper canines are completely or mostly sheathed by the upper lip and the mouth is not clenched shut but slightly agape. Go ahead and peruse google images of large felids and see where the bias lies in terms of canines exposed or not. I double dog dare you.

Other facial features that the Chauvet lions display that are not concordant with the Isturitz statue are that the ears of the cave lion are rounded while the statuette's ears are very distinctively pointed. The spotted pelage and what appears to be a countershaded line along the torso in the statuette also do not match well with the striped pelage that has been suggested for cave lions from ancient cave art. This is a notable omission and Anton et al. deserve to be called out for not mentioning these anatomical incongruity. ( Peer review fail #3 & #4)

One of the more interesting ideas put forth is that the figurine represents a cub due to the big eyes. However I am not sure if those eyes are just stylized and if such a bold chin would be consistent with a cub lion. This idea might explain the spotted pelage as cub lions have spots and then lose them; on the other hand the cubs of striped tigers are not born spotted they are always striped.

And finally the tail. Homotherium has a bobtail while cave lions do not. Is the tail broken off in the statuette? I don't know, we can't go back and analyze which is why it probably should not have got into the scientific literature in the first place!!

Finally it is interesting that - if cave lions had manes like modern lions - a female lion would be chosen for the statuette, and not a male. I mean if you look at iconographic imagery of lions made by humans the male lion predominates in representation. It is larger, has a striking mane, is more powerful and the symbology to "warlike" civilizations is obvious; but perhaps the female lion was actually the preferred symbolic analogy used by paleolithic cultures and they in fact had a different set of cultural values than modern humans...

As you can see we are clearly in the subjective zone on this one. Switek says it takes a lot of special pleading to infer that the statuette represents Homotherium but I say it takes just as much, if not more, special pleading to infer it as a cave lion.

Look the statuette can be argued about until the cows come home - which I will abstain from doing so in the comments section so don't even try and tempt me... But it is a compelling and interesting story.

On a bigger level this whole discourse is a great lesson in how bias can go unseen and get propagated seemingly without question.

If you go back and read the selection I culled from the Switek article he states his bias right up front:

"... and there is no reason to believe that the canines would have been covered by lips in life."

Let me just refresh you on the talking points on why large lips covering teeth should not only be the belief but the null hypothesis that should be disproven in extinct mammalian carnivorans; all modern terrestrial mammalian carnivornans sheath most or all of their teeth in lips and flesh (EPB); an extensive and proportionate "nerve pad" inferred from large infraorbital foramen located proximate to canine entry assists in vulnerable and precise tooth entry; protection of teeth, especially canines, from breakage and grit; osteological evidence of mandibular flange in sabertoothed predators infers complimentary protection from above.

It may appear that I am picking on Brian here but really he is just a fill-in for many of our biases favoring tooth exposed extinct predators, including until recently myself. Darren Naish seemed to have been favorable to the Isturitz statuette representing a late surviving Homotheriumwhen he discussed it way back in 2006. However after Anton argued otherwise Darren seems to have changed his mind in 2010. However if you look through the comments section in that post you will see that longtime Tet Zoo commentator Jerzy makes many of the same arguments (except I don't think the canine teeth need fit into pockets like in male baboons as suggested by Mazak as well) I am making and calls out several omissions from the Anton paper:

Evidence of Morphological Features Evolving in Tandem With Increasing Canine Length In Sabretooth Predators

As cultural creations as much or even more so than scientific ones it is always useful to brace yourself for the shock and cognitive dissonance of a cherished and loved extinct animal taking on a radical, bizarre new look. We see this startling and immediate transformation but I don't think that we always appreciate that an organism is the product of evolutionary pressures and compromises occurring to it and molding it over millions of years. From our perspective large lips smothering a Smilodon's face appear to evolve over night but in reality the large lips and large teeth would be evolving in tandem as each feature influenced and reinforced the other in a feedback loop. It is only the shock and awe of seeing this change so sudden and profound that we rebel against it.

My contention that increasing lips evolved in tandem with increasing canine size is bolstered by a study showing the exact same correlation of increasing forequarter and forearm strength in sabertoothed predators occurring in concert with increasing canine length. Powerful Arms Saved Sabretoothed Killers' Fearsome Fangs, Study Shows

Julie Meachen-Samuels:

"I found that they had very thick humerus cortical bone, much thicker than any non sabertoothed cat living or extinct... I hypothesized that this extreme cortical thickness was correlated with the extremely long sabers. The robust limbs allowed Smilodon to restrain its prey so that it would be able to make a killing bite without damage to its saber teeth... These traits evolved as not only a suite of characters but as a viable distinctive prey killing strategy several times independently. This combination probably evolved several times because the predators that could best protect and preserve their teeth during prey killing survived longer and could have more offspring, thereby making this combination of long teeth and strong forelimbs a winning combination."

So should I connect the dots? Canines start growing a bit longer, lips evolve in tandem to sheath, protect, lubricate, and provide optimal tactile sensory usage. Forelimbs and forequarters get more robust to further the safety and efficiency of the kill. Canines grow a little longer still as do the lips and forequarters. The animals that can best protect their teeth and live longer reproduce the most even if it is just by incremental percentages. Repeat, repeat, repeat until you get something that looks like this:

The thing is you can still haz ur scary Smilodon even with the lips covering the fangs. It is often times what you don't see that scares you the most. If anything the big, jangly jowels add a surreal and disturbing touch. And it is all too easy to imagine that upper lip being pulled back to reveal that staggering dental load just glistening with lubricating juices and ill intent.

So just one more time to hammer down the talking points:

Facial tissue completely or mostly sheathing the upper canines as is corroborated by ALL extant terrestrial mammalian carnivorans and is the best null hypothesis; exposed and constantly growing tusked mammals use their non-serrated tusks for coarse hacking, chopping, digging, combat and display and are an inferior analog to sabertooth canines and need not be considered as they fail in comparison along nearly every metric; the clouded leopard which has long canines comparable to many sabertoothed predators covers its canines completely; all five radiations of sabertooth predators display osteological evidence of protective sheathing on the lingual inferior aspect of the canine via a mandibular flange - a logical evolutionary inference is that protection for the superior labial aspect of the canine was also selected for in the presence of a large fleshy upper lip; the presence of this large fleshy upper lip is corroborated osteologically by the relatively large infraorbital foramen found in all sabertooth predators; this large infraorbital foramen supplies the blood and nerve supply to an extremely large and sensitive "nerve pad"; the extremely innervated nerve pad provides tactile support to make precise and crucial placement of canine entry for bite; such tactile support would be diminished in sabertooths depicted with modest sized upper lip region as this area would be scrunched away from the bite area when the mouth is opened and it would be the vulnerable canines that would "feel out" where to bite; large lips and supporting nerve pad evolved in lock step with increasingly large canines and forequarter strength for maximum safety and efficiency in these highly precise yet vulnerable predators.

And I did not even mention the benefits of; having your serrations free of grit & abrasives; accruing scent particles on a larger "environmental swab"; lubrication for cleaner cutting; and preventing excess moisture loss.

Or you can keep your feebly lipped, tooth exposed, non-tactile, maladaptive, vulnerable, culturally enshrined, and just plain weird looking sabertooth predator. But I say you are holding onto a dream... Yup puny lipped advocates it is you and not I that need be on the defensive on this one. Your creature is the myth - not mine. Script. Flipped.

"It is the responsibility of the scientific paleo-illustrator to make sure that his images rigorously transmit the knowledge that the paleontologists have gathered from specific extinct species."

-Mauricio Anton

*Clarification. I can already see some people misconstruing what I am suggesting with the notion that the upper canines fit into "pockets" formed by the lower lip and the mandible as suggested by Mazik. I don't think this was the case as at all. The upper canines simply rested against a more extensive lower lip region that was very durable and tough tissue - again not unlike the tough, elastic usually dark lips of domestic breeds of dogs that have had this feature artificially enhanced. Also don't confuse what I am suggesting with the debunked notion of G.J. Miller who suggested a quasi- "bulldog" look but for other reasons than what I am suggesting. Miller thought that the lip was retracted backwards to allow proper carnassial use due to the canine length. However this premise is faulty because such a lip would cut right into the masseter muscle and it is not needed anyways as modern felids are able to use their carnassial teeth without opening their mouth all the way.

References

Andersson K, Norman D, Werdelin L (2011) Sabretoothed Carnivores and the Killing of Large Prey. PLoS ONE 6(10): e24971. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0024971

Anton, M. 2013. Sabretooth. Indiana University Press

Anton, M., Salesa, M.J., Turner, A., Galobart, A., Pastor, J.F. 2009. Soft tissue reconstruction of Homotherium latidens (Mammalia, Carnivora, Felidae). Implications for the possibility in paleo-art. GEOBIOS 42 (2009) 541-551

Cohen, Jenny 2012. Powerful Arms Saved Saber - Toothed Killer's Fearsome Fangs, Study Shows. January 4, 2012.

Meachen-Samuels, J.A. 2012. Morphological convergence of the prey killing arsenal of sabertooth predators. Paleobiology 38(1): 1-14

Naish, Darren. 2006. The late survival of Homotherium confirmed, and the Piltdown cats. Tetrapod Zoology. Thursday, March 9 2006

Naish. 2010. Tetrapod Zoology Book One is Here At Last. Tetrapod Zoology. October 7, 2010

Switek, Brian. 2010 Facing Homotherium. WIRED. November 18, 2010

Cheers!!

Support me on Patreon.

So in this post I am going to eschew that waffling, tentative tone and go right in for the kill shot. Yup names will be named. Things will get messy. Feelings might get hurt. Reputations might get questioned. Including my own but that's ok I am willing to play the villain.

But...

I did go through some real searching in how I wanted to approach this post. I mean the good and bad thing about blogging is you can see where and how traffic gets shuffled to your site which means that you get to read the things people say about you - and it does affect you deeply. In various form I have been called overly speculative, aggressive, a bit of a bully, not to be taken seriously, and sort of a mean and angry guy. And I get it why people say these things about me. I have always indulged in what I consider plausible speculative possibilities. I fully admit that I have a bit of chip on my shoulder that has a lot to do with not getting recognition and blogging not being recognized as a form of science communication on par with the "peer reviewed word" but I think that is changing. I have no problem calling out the "luminaries" of the field when they leave out data, make less than ideal suggestions, and use the weight of their name as a bully pulpit. At the same time I am fully confident that if you spent any amount of real time in the flesh with me you would come away with a perhaps very different or at least more nuanced impression of me than the above characterizations. I have also seen it written that I am too passionate and excited about my own ideas. "Too passionate and excited"... think about that for a second.... I've said it before and I'll say it again there is a little too much tone policing in paleo these days when passion and excitement are discouraged. If you have not noticed science is in a war and is failing to create the excitement, fun, enlightenment, fullfillment, and yes mysticism that other forms of belief are giving people for better or worse.

Never the less it is a hard thing to tell someone that a significant chunk of their life's work is obsolete and you have to be just a little bit of a bully to do so.

To quote the great "Nature Boy" Ric Flair: "To be the man you gotta beat the man!! Whoo!"

To really s - p - e - l - l it out for you I am make the allusion to "professional wrestling" to evince the level of venom, anger, and aggression in my heart - none at all really. It is all a bit of a bluff theatrical arrangement. Of course tone has a way of getting misconstrued in writing. And no, I am not on cocaine.

That being said I am really going out to pick a fight on this one and you better believe I am coming in swinging, guns blazing, and with the gusto!!

|

| La Brea Tar Pits. Charles R. Knight public domain |

There is a bit of a problem in sabertooth paleontology. An echo chamber has evolved where one man and one man only seems to dominate the narrative over this eco-morphological grouping of animals. And that man is Mauricio Anton whose books, papers, artwork, and blogging have cast a heavy influence on our view of these animals. Truth be told he deserves the recognition and there is good reason for this respect. His artwork is captivating and in a class of its own. His books are well written, engaging, and straddle the difficult line between being overly technical and approachable. However when the artistic and scientific leanings of only one man become the main voice heard or recognized that is never a good thing in any social or scientific activity. Biases can and do slip through. Unconscious memes passed on.

|

| Charles R. Knight. Public Domain |

In the case of this one aspect of sabertooth predators that I will be addressing the cultural transmission of this meme has gone on and on for some time now, Anton as the de-facto principal conveyor of sabretooth aspect and imagery merely inherited it from Knight and paleoartists/paleontologists of the past. It is not really his creation. However Anton "is the man" in sabertooth paleobiology and paleo-art. Heavy lies that throne and any reappraisal of sabretooth anatomy and imagery can not eschew mention of his influence. There really is no way to avoid going through him.

Enough beating around the bush, it's time for Mr. Sabertooth Tiger to get some self respect, stop walking around all exposed, have some decency AND COVER UP THOSE DAMN DAGGERS!!

Yup, sabertooth predators its time to grow up and cover yourself properly with nice big luscious lips sheathing your cherished daggers. You know, like is the case for EVERY EXTANT MAMMALIAN TERRESTRIAL CARNIVORAN. Is that phylogenetic bracketing enough for you? Truth be told phylogenetic bracketing should never be looked at as the ultimate truth, just a rough road-map. It is always better to take a pluralistic approach imbuing the EPB with a heavy dose of adaptationism - Stephen Jay Gould be damned. That is the approach I took with my last post on a heavily lipped T. rex and it is the method I will take here. One caveat of the adaptationism approach is that the feature you are looking at should be one that has a strong influence on survivorship and hence sexual success. So yeah, I think a feature intimately influencing, protecting, lubricating, and assisting in killing via those precious daggers counts in that regard in a very robust way.

"But what about elephants, walrus, and other tusked mammals? Their teeth are exposed all the time."

|

| Pacific Walrus. Cape Pierce Public Domain |

You know, I have to admit to throwing up a little in the back of my mouth whenever I hear this argument trumpeted out again and again. First of all it is moving further and further away from the extant phylogenetic bracket. We already have tons of living extant carnivorans to infer from, all of them cover their teeth completely or mostly. Even the clouded leopard the cat >most< often compared or likened to sabertoothed predators covers its teeth with a nice set of lips. Secondly, tusks don't even compare in form or function to saber toothed canines. Tusks are robust, coarse choppers for plowing into trees, roots, gouging into sediments, and >most importantly< fighting with and intimidating rivals. That they are always exposed has a lot to do sexo-social signalling. Sabertooth canines do none of these activities, are often serrated, and are intrinsic to survivorship. Tusks are always out and on display because a better strategy for always getting into costly and risky fights is to bluff your way to the top by always having your weaponry out, exposed, and in full view. Sabertooth daggers were not sexo-social displays and/or fighting tools, an argument Anton (among others) has summarily dismissed. Finally tusks keep growing in many animals that have them. Sabertooth predators had no such luxury. Comparing sabertooth daggers to tusks is like comparing a surgeons scalpel to a machete - a machete that keeps growing back. As you can tell I don't take this argument very seriously. In fact I would call it special pleading.

|

| clouded leopard. credit Vearl Brown CC2.0 |

|

| clouded leopard skull |

We already have numerous and unequivocal osteological evidence of direct evolutionary pressure on sabertooth predators to sheath and protect their cutlery.

|

| Rubidgea. credit Ghedoghedo CC3.0 |

|

| Thylacosmilus atrox. credit Claire Houck AMNH. CC2.0 |

.JPG.png/800px-Machaeroides_eothen_(cropped).JPG.png) |

| Machaeroides eothen. credit Ghedoghedo. CC |

|

| Pogonodon platycopis. Edward Drinker Cope public domain |

|

| Eusmilus. wiki commons |

|

| Hometherium crenatidens fabrini. Public Domain |

Above you see examples of the bony correlate in all six of the respective sabertooth predator radiations; gorgonospid synapsids; thylacosmilidaen metatherians; machaeroidinean creodonts; nimravidaen carnivorans; barbourofelidaen carnivorans; and felidaen carnivorans.

It is in the form of the mandibular flange. In some examples it is quite profound, in others it is a little incipient. However it occurs in all radiations of sabertooth predators giving us a strong example of convergent evolution. But to expect evolutionary pressures to exert an influence on just the mandibular, inferior section of the tooth and not expect protection from above - where blows are most likely to come from? Evolution are you drunk? Should we really expect evolutionary pressures to exert an influence on protecting just the bottom aspect of the dagger and not the top? Really, you think so? When you blink does your eyelid only cover half of your eyeball? Does a turtle carapace only protect half of the turtle? Does your cranium only cover half of your brain? Sounds like a very half-assed protective strategy to me.

Instead I would argue a much more robust inference is that ALL sabertooth predators protected their cutlery from above and below. Some species show evidence of the inferior protection via the mandibular flange which itself was sheathed in a very rugged and durable layer of "skin" a lot like the darker area of the jowls you see in your own pet dog. The upper protection would come from a fleshy expansion of the upper lip region - just as you see in any felid or carnivoran today - except larger. As sabertooth predators evolved larger and longer daggers so to did the soft anatomy that protected and assisted them evolve in tandem. Pull up the upper lips to expose teeth and bite. Let lips go loose when teeth are not in use. That a Smilodon with big droopy facial lips seems shocking now is only an artifact of the cultural shock of multiple decades of toothed exposed iconography.

Such protection would not be 100% but I would hedge my inference in favor of protection rather than not. If a feature can evolve that can assist in the struggle for survival, then it should be there.

"How dare you compare sabertooth lips to the lips of artificially selected dogs and cats? Stop it."

Nope, not stopping. The reason I posit this distinctive bulldog looking Smilodon is that artificially bred mammalian carnivorans aptly demonstrate that there is a lot of plasticity in the facial region of these animals. That humans bred them this way for looks, for better scenting abilities, for whatever... I don't really care. All that these domestic breeds show me is that giving the evolutionary context and pressures (i.e. fleshy lips to protect large dentition) there is the genetic potential in mammals that such a look >could< evolve in a wild extinct sabertoothed animal. That the bulldog look comes about is, well, try drawing a sabertooth yourself and the only prerequisite is that the teeth are mostly or completely covered by lips and it is hard to avoid the bulldog look.

Extensive Lips & Fleshy Oral Tissues Allows Enhanced Proprioception of Sabertooth Head & Daggers in Relation to Prey. We Have Direct Osteological Evidence Of This Too.

As tool using, reduced canine having primates I think we often fail to appreciate the risks incumbent upon biting down into something that does not want to get bitten into. I mean, it is a pretty simple thought but revelatory at the same time. You are literally ramming your most vulnerable external body part into another organism latching onto and often holding onto them. Let me restate that again: your most vulnerable body part is in direct line of fire for whatever you are attempting to latch onto. Remember you have to do this again and again to make a living so to speak ecologically. All of these pitfalls would be especially true for sabertooth predators which seem to show a penchant for not only large, strong and retaliatory prey but direct and relatively prolonged contact (i.e. not a bite and flee predator but a tackle, subdue, and bite predator) in which their vulnerable daggers are put into jeopardy. If there is ANY advantage you can potentially and reasonably evolve that helps you to make a killing safer, quicker, and more efficiently then that evolution will likely occur and the inference is a robust one.

Large fleshy lips and oral tissue not only provide a better means of protection from struggling prey (although not 100%) but they also provide a larger and more extensive tactile surface area to position the teeth for efficient and safe biting.

Let me just quote Anton directly here from his book Sabretooth (pp 178-79 Sabretooths as Living Predators):

"One consistent feature of most sabertoothed carnivores is the relatively large size of the infraorbital foramen... (discussion of potential muscular insertion, rodents, Barbourfelis)... there are other structures that pass through infraorbital in all mammals - specifically, the infraorbital nerve, veins, and arteries. The infraorbital nerve is a branch of the maxillary nerve, and it provides sensory nerve endings to the whiskers. Once the nerve crosses the canal, it begins to branch; and when it reaches the roots of the whiskers, it forms a true "nerve pad," creating a characteristic swelling on the sides of the muzzles of many mammals. Thus, one tempting explanation for the large diameter of the opening in sabertooths would be the presence of very well developed, especially sensitive whiskers with rich innervation."

While Anton later tempers his stance mentioning issues of direct proportionality he does mention that " the relationship between the development of the foramina and the function of the infraorbital nerve is widely accepted among zoologists."

I would go further and posit that the reason the infraorbital foramen is relatively larger in sabertooths than other predators is that not only was the "nerve pad" more sensitive - it was also absolutely larger than the nerve pad in extant felids. Why such a large and sensitive nerve pad would be needed in these predators is fairly obvious in terms of making precise and safe incisions into struggling and retaliatory prey that could easily snap off or damage your cutlery.

Anton pp 179:

"... the killing bite of sabertooths must have been quite precise in order to avoid accidents involving lateral torsion or hitting a bone in the prey, which could cause the sabretooth to break a canine. Since the target area of the bite would be outside the predator's visual field, the tactile information provided by the whiskers would be especially useful for the precise control of the biting motions. Modern cats are able to move their whiskers thanks to well developed piloerector muscles, and during the killing bite the whiskers are usually directed forward, enveloping the bitten area in a sensitive net of hairs (Leyhausen, 1979). Given the additional risks imposed by fragile sabers, improved perception would be a useful trait for the sabretooths."

I like and agree with everything Anton says here. I just differ from him in inferring an absolutely larger "nervepad" that would ultimately be more adaptive than the smaller nerve pad he prefers that only partially cover the daggers as depicted in his and all others' paleoart. I can already picture some people saying "well what if the whiskers were just longer?" nah, always better to have the tactile ability and protection. That is the more adaptive and reasonable inference not whiskers creeping down like daddy-long legs.

|

| credit Nick Farnhill. CC2.0 |

As you can see in the above pic of a cheetah throat clamping Thompson's gazelle - in which the canines clamp shut the windpipe and kill by suffocation - the sensitive nerve pad is deeply enmeshed in this activity. Indeed as the bite occurs in a blind spot for the cat it is the nerve pad, especially via the whiskers, that most accurately dictates to the predator where and how the clamp should be applied. Let's think about this for a second. Many modern large felids clamp the windpipe shut with their relatively stout and blunt canines. That is a pretty refined and delicate approach and the utility of having the sensitive muzzle and whiskers enmeshed in close proximity to the bite area is self evident. However when we contrast this method with how sabertoothed predators - especially the "dirk toothed" cats likely killed - they were looking to inflict massive trauma to the general fleshy region of the neck (but also possibly abdomen). Whether the killing stroke severed arteries or the windpipe or both not really important as the end result is the same - death. So if you think about it the killing method of such sabertooth predators is less precise than many modern felids - as long as they get their bite in the general non-bony area of the neck (or abdomen) they good. SO WHY WOULD THE INFRAORBITAL FORAMEN BE RELATIVELY LARGER IN SABERTOOTHS? The logical conclusion is that the "nerve pad" was not relatively more sensitive per surface area than modern felids, it was in fact absolutely larger than modern felids and likely equally innervated and fed with adequate blood supply. This soft tissue adaptation would cover up those precious daggers and provide the tactile support to place the daggers in the right spot to make a killing stroke without risking torsional twisting of prey or bone chipping.

Additionally when we consider how this biting action would look and function in a sabertooth with the traditionally depicted modest sized nerve pad a real dilemma occurs. Due to the large size of the daggers - especially extreme in genera like Smilodon - the sensitive nerve pad would be scrunched up and pushed away from the bite area and not very useful for "feeling out" the best place to position a bite when the mouth was open. Indeed it would be the large teeth "feeling things out" - exactly the problem sabertoothed predators want to avoid!!

|

| - http://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0024971 |

You can easily see what I am talking about using this kinematic illustration above. The sensitive nerve pad would be nowhere near the bite area in traditionally depicted sabertoothed predators. But if we infer a large upper lip and nerve pad that completely or nearly completely sheathed the upper teeth even when the mouth is opened then you have a much more efficient and safer ability to "feel out" where and when to engage the teeth with prey. In this manner the teeth are protected and sheathed until the final split second before impact and the upper lip is pulled back to reveal the daggers. The tough and elastic lip need not even be pulled back that far because as the daggers are plunged into prey the body of the prey itself would simply push back against the lip sliding them back further. Large upper lips provide the most safe, efficient, and osteologically corroborated method of biting possible.

"If only we had evidence for sabertooth appearance via cave-art or other ancient depictions" ... well maybe we do.

Yup it is time we revisit the potential Rosseta Stone of sabertooth life appearance: the paleolithic statuette from Isturitz.

Now I want to make it clear - this is an artistic representation by Mauricio Anton based upon the rendering of Czech paleontologist Vratislav Mazak who himself saw representations of the original statuette in 1970. Long story short nobody actually has the statuette as it has been lost since at least the early part of the 20th century. As the statuette has been lost and been redrawn at least two times, maybe even three times as Mazak himself is said to have only seen "representations" of it, the logical conclusion is that there is a lot of ambiguity in this piece. Furthermore as the original piece can not be directly observed i.e. it can not be "tested" by others it should be in fact stricken from scientific discourse. I mean, am I wrong? Is that not the argument put forth why "private fossil specimens" can not be part of the recognized science as they can not be first hand analyzed, observed, and tested by all parties... am I missing something here? Never the less the Isturitz statuette representation has made it through peer review and is part of the "recognized" scientific literature despite the inability to test it (peer review fail #1).

In his paper reconstructing the musculature and facial anatomy of Homotherium latidens (Anton, et al. 2009) steer away from Mazak's interpretation of the Isturitz statuette representing a late surviving Pleistocene Homotherium and instead side with the original interpretation of cave lion. In Facing Homotherium Brian Switek summarizes their argument succinctly:

It should be noted that this analysis dovetails into the facial reconstruction that Anton et al perform on Homotherium in the same paper.

Compared to:

And a cave lion representation:

.jpg/1280px-Lions_painting%2C_Chauvet_Cave_(museum_replica).jpg) |

| Replica Chauvet Cave Lions, France |

While Anton et al. do provide some compelling arguments concerning body proportion and the lack of a sloped back in the model as Homotherium would have in life (sort of like a spotted hyena) these gross anatomical inferences can be explained by the lack of forefeet in the statuette which may influence how the posture is meant to be; the possibility the figure represents a dead or lying felid; and simple errors on the part of the artist.

On the chin argument I find it less than compelling that the strong chin and large lower jaw represents the tuft of hair on a lion. It just looks too prominent and large in my eyes and is more consistent with the mandibular flange of Homotherium. There is no abrupt transition from the chin to the neck line as should be expected if the chin was simply a tuft of hair. Furthermore the manner in which Anton et al reconstruct the jaw in Homotherium is inconsistent with how we or most animals actually hold the jaw in neutral pose. They pose it in "extreme" jaw closure as if the animal would be walking around clenching its teeth shut - similar to the argument put forth on extreme jaw closure in tyrannosaurids and other theropods debunked in my last post. I suspect most animals (including you as you read this unless you are like really mad right now ;') have their jaws just slightly agape in the neutral pose. This would dissuade the need for the teeth to fit into pockets of flesh in the lower jaw as suggested by Mazak and argued against by Anton et al. (sort of like male baboons) but instead the whole upper canine would simply be sheathed by the upper lip/nerve pad. When the jaw was fully closed it would simply lie against the thick tough, elastic, and lubricated skin of the lower jaw. Just like a clouded leopard which, by the way looks to have canines at least as big or bigger as Homotherium relative to its head size.

There is a bit of a tendency in paleo for people to see beautifully rendered muscular and skeletal reconstructions of extinct animals and take them a little too literally. When in reality there is a lot of guesswork and biases at play in even the most "rigorously" reconstructed extinct animal no matter how aesthetically appealing. In the paper Anton et al. provide a list of references for how they reconstruct the soft tissue for Homotherium latidens:

"For soft tissue reconstruction we followed the methodology outlined in our previous works (Anton, 2003; Anton & Galobart, 1999; Anton & Sanchez, 2004; Anton et al., 1998; Turner & Anton, 1998)."

Notice any pattern there? If a guy with the last name of Anton is the lead author of the paper and the source methodology for reconstructing soft tissue is also culled from a guy with the same last name it is not unreasonable to suspect a certain unanalyzed bias to seep through? Could there be a bit of an echo chamber here?

Anton et al., also cite the extant phylogenetic bracket as defined by Witmer as a means to infer soft tissue. But what this method lacks is putting soft tissue through the lens of adaptationism.

Anton et al. also assert that if the canines are long enough they should be seen passing past the upper lip. As evidence for this assertion they cite one example of a canine peeking past the upper lip in a dead lioness they dissected.

Now, you need not be a statistician to realize that when N=1 that is not a very large pool of a sample size to draw meaningful data from. Additionally, you need not be a mortician to realize that when stuff dies things change. Muscles grow tighter drawing back soft tissues. Mouths clench shut potentially. Anton et al. did not account for this or even mention these obvious pitfalls on drawing anatomical conclusions from a cadaver of one sample size (peer review fail #2 ). Better to look at live animals. And when you look at live carnivorans - especially felids - the upper canines are completely or mostly sheathed by the upper lip and the mouth is not clenched shut but slightly agape. Go ahead and peruse google images of large felids and see where the bias lies in terms of canines exposed or not. I double dog dare you.

Other facial features that the Chauvet lions display that are not concordant with the Isturitz statue are that the ears of the cave lion are rounded while the statuette's ears are very distinctively pointed. The spotted pelage and what appears to be a countershaded line along the torso in the statuette also do not match well with the striped pelage that has been suggested for cave lions from ancient cave art. This is a notable omission and Anton et al. deserve to be called out for not mentioning these anatomical incongruity. ( Peer review fail #3 & #4)

One of the more interesting ideas put forth is that the figurine represents a cub due to the big eyes. However I am not sure if those eyes are just stylized and if such a bold chin would be consistent with a cub lion. This idea might explain the spotted pelage as cub lions have spots and then lose them; on the other hand the cubs of striped tigers are not born spotted they are always striped.

And finally the tail. Homotherium has a bobtail while cave lions do not. Is the tail broken off in the statuette? I don't know, we can't go back and analyze which is why it probably should not have got into the scientific literature in the first place!!

Finally it is interesting that - if cave lions had manes like modern lions - a female lion would be chosen for the statuette, and not a male. I mean if you look at iconographic imagery of lions made by humans the male lion predominates in representation. It is larger, has a striking mane, is more powerful and the symbology to "warlike" civilizations is obvious; but perhaps the female lion was actually the preferred symbolic analogy used by paleolithic cultures and they in fact had a different set of cultural values than modern humans...

As you can see we are clearly in the subjective zone on this one. Switek says it takes a lot of special pleading to infer that the statuette represents Homotherium but I say it takes just as much, if not more, special pleading to infer it as a cave lion.

Look the statuette can be argued about until the cows come home - which I will abstain from doing so in the comments section so don't even try and tempt me... But it is a compelling and interesting story.

On a bigger level this whole discourse is a great lesson in how bias can go unseen and get propagated seemingly without question.

If you go back and read the selection I culled from the Switek article he states his bias right up front:

"... and there is no reason to believe that the canines would have been covered by lips in life."

Let me just refresh you on the talking points on why large lips covering teeth should not only be the belief but the null hypothesis that should be disproven in extinct mammalian carnivorans; all modern terrestrial mammalian carnivornans sheath most or all of their teeth in lips and flesh (EPB); an extensive and proportionate "nerve pad" inferred from large infraorbital foramen located proximate to canine entry assists in vulnerable and precise tooth entry; protection of teeth, especially canines, from breakage and grit; osteological evidence of mandibular flange in sabertoothed predators infers complimentary protection from above.

It may appear that I am picking on Brian here but really he is just a fill-in for many of our biases favoring tooth exposed extinct predators, including until recently myself. Darren Naish seemed to have been favorable to the Isturitz statuette representing a late surviving Homotheriumwhen he discussed it way back in 2006. However after Anton argued otherwise Darren seems to have changed his mind in 2010. However if you look through the comments section in that post you will see that longtime Tet Zoo commentator Jerzy makes many of the same arguments (except I don't think the canine teeth need fit into pockets like in male baboons as suggested by Mazak as well) I am making and calls out several omissions from the Anton paper:

Evidence of Morphological Features Evolving in Tandem With Increasing Canine Length In Sabretooth Predators

As cultural creations as much or even more so than scientific ones it is always useful to brace yourself for the shock and cognitive dissonance of a cherished and loved extinct animal taking on a radical, bizarre new look. We see this startling and immediate transformation but I don't think that we always appreciate that an organism is the product of evolutionary pressures and compromises occurring to it and molding it over millions of years. From our perspective large lips smothering a Smilodon's face appear to evolve over night but in reality the large lips and large teeth would be evolving in tandem as each feature influenced and reinforced the other in a feedback loop. It is only the shock and awe of seeing this change so sudden and profound that we rebel against it.

My contention that increasing lips evolved in tandem with increasing canine size is bolstered by a study showing the exact same correlation of increasing forequarter and forearm strength in sabertoothed predators occurring in concert with increasing canine length. Powerful Arms Saved Sabretoothed Killers' Fearsome Fangs, Study Shows

Julie Meachen-Samuels:

"I found that they had very thick humerus cortical bone, much thicker than any non sabertoothed cat living or extinct... I hypothesized that this extreme cortical thickness was correlated with the extremely long sabers. The robust limbs allowed Smilodon to restrain its prey so that it would be able to make a killing bite without damage to its saber teeth... These traits evolved as not only a suite of characters but as a viable distinctive prey killing strategy several times independently. This combination probably evolved several times because the predators that could best protect and preserve their teeth during prey killing survived longer and could have more offspring, thereby making this combination of long teeth and strong forelimbs a winning combination."

So should I connect the dots? Canines start growing a bit longer, lips evolve in tandem to sheath, protect, lubricate, and provide optimal tactile sensory usage. Forelimbs and forequarters get more robust to further the safety and efficiency of the kill. Canines grow a little longer still as do the lips and forequarters. The animals that can best protect their teeth and live longer reproduce the most even if it is just by incremental percentages. Repeat, repeat, repeat until you get something that looks like this:

|

| Duane Nash. EatYourKittenSmilodon |

The thing is you can still haz ur scary Smilodon even with the lips covering the fangs. It is often times what you don't see that scares you the most. If anything the big, jangly jowels add a surreal and disturbing touch. And it is all too easy to imagine that upper lip being pulled back to reveal that staggering dental load just glistening with lubricating juices and ill intent.

So just one more time to hammer down the talking points:

Facial tissue completely or mostly sheathing the upper canines as is corroborated by ALL extant terrestrial mammalian carnivorans and is the best null hypothesis; exposed and constantly growing tusked mammals use their non-serrated tusks for coarse hacking, chopping, digging, combat and display and are an inferior analog to sabertooth canines and need not be considered as they fail in comparison along nearly every metric; the clouded leopard which has long canines comparable to many sabertoothed predators covers its canines completely; all five radiations of sabertooth predators display osteological evidence of protective sheathing on the lingual inferior aspect of the canine via a mandibular flange - a logical evolutionary inference is that protection for the superior labial aspect of the canine was also selected for in the presence of a large fleshy upper lip; the presence of this large fleshy upper lip is corroborated osteologically by the relatively large infraorbital foramen found in all sabertooth predators; this large infraorbital foramen supplies the blood and nerve supply to an extremely large and sensitive "nerve pad"; the extremely innervated nerve pad provides tactile support to make precise and crucial placement of canine entry for bite; such tactile support would be diminished in sabertooths depicted with modest sized upper lip region as this area would be scrunched away from the bite area when the mouth is opened and it would be the vulnerable canines that would "feel out" where to bite; large lips and supporting nerve pad evolved in lock step with increasingly large canines and forequarter strength for maximum safety and efficiency in these highly precise yet vulnerable predators.

And I did not even mention the benefits of; having your serrations free of grit & abrasives; accruing scent particles on a larger "environmental swab"; lubrication for cleaner cutting; and preventing excess moisture loss.

Or you can keep your feebly lipped, tooth exposed, non-tactile, maladaptive, vulnerable, culturally enshrined, and just plain weird looking sabertooth predator. But I say you are holding onto a dream... Yup puny lipped advocates it is you and not I that need be on the defensive on this one. Your creature is the myth - not mine. Script. Flipped.

"It is the responsibility of the scientific paleo-illustrator to make sure that his images rigorously transmit the knowledge that the paleontologists have gathered from specific extinct species."

-Mauricio Anton

*Clarification. I can already see some people misconstruing what I am suggesting with the notion that the upper canines fit into "pockets" formed by the lower lip and the mandible as suggested by Mazik. I don't think this was the case as at all. The upper canines simply rested against a more extensive lower lip region that was very durable and tough tissue - again not unlike the tough, elastic usually dark lips of domestic breeds of dogs that have had this feature artificially enhanced. Also don't confuse what I am suggesting with the debunked notion of G.J. Miller who suggested a quasi- "bulldog" look but for other reasons than what I am suggesting. Miller thought that the lip was retracted backwards to allow proper carnassial use due to the canine length. However this premise is faulty because such a lip would cut right into the masseter muscle and it is not needed anyways as modern felids are able to use their carnassial teeth without opening their mouth all the way.

References

Andersson K, Norman D, Werdelin L (2011) Sabretoothed Carnivores and the Killing of Large Prey. PLoS ONE 6(10): e24971. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0024971

Anton, M. 2013. Sabretooth. Indiana University Press

Anton, M., Salesa, M.J., Turner, A., Galobart, A., Pastor, J.F. 2009. Soft tissue reconstruction of Homotherium latidens (Mammalia, Carnivora, Felidae). Implications for the possibility in paleo-art. GEOBIOS 42 (2009) 541-551

Cohen, Jenny 2012. Powerful Arms Saved Saber - Toothed Killer's Fearsome Fangs, Study Shows. January 4, 2012.

Meachen-Samuels, J.A. 2012. Morphological convergence of the prey killing arsenal of sabertooth predators. Paleobiology 38(1): 1-14

Naish, Darren. 2006. The late survival of Homotherium confirmed, and the Piltdown cats. Tetrapod Zoology. Thursday, March 9 2006

Naish. 2010. Tetrapod Zoology Book One is Here At Last. Tetrapod Zoology. October 7, 2010

Switek, Brian. 2010 Facing Homotherium. WIRED. November 18, 2010

Cheers!!

"A Long habit of not thinking a thing wrong, gives it a superficial appearance of being right, and raises at first a formidable outcry in defense of custom". Thomas Paine

Support me on Patreon.

Like antediluvian salad on facebook. Visit my other blog southlandbeaver.blogspot

Watch me on Deviantart @NashD1. Subscribe to my youtube channel Duane Nash.